Chapter 2 Animal and environment

2.1 External environment

Animal never separates from the stimuli from outside. Basically, animals can find food, shelter, protection, and mates from the environment called habitat. The animal habitat includes both phisical (non-living) and biotic (livinig) components (Table 2.1).

Animal habitat is constantly changed over time. Not only natural disasters (eruption of volcano, earthquake, tsunami, and wildfire), also human activity can affect the animal habitat. Unlike the wildlife, the environment of domesticated animals (such as cow, pig, poultry, and dog) that raised in the facility are controlled by the human. In the domestic animals, the external environment includes both physical (e.g. housing, feeder, paddock, fence, and noise) and biotic (e.g. human, mate, and feed ingredients) components.

| Physical | Biotic |

|---|---|

| Temperature | Plant matter |

| Humidity | Predators |

| Oxygen | Parasites |

| Wind | Competitors |

| Soil | Individuals of the same species |

| Light intensity | |

| Elevation |

2.1.1 Biome

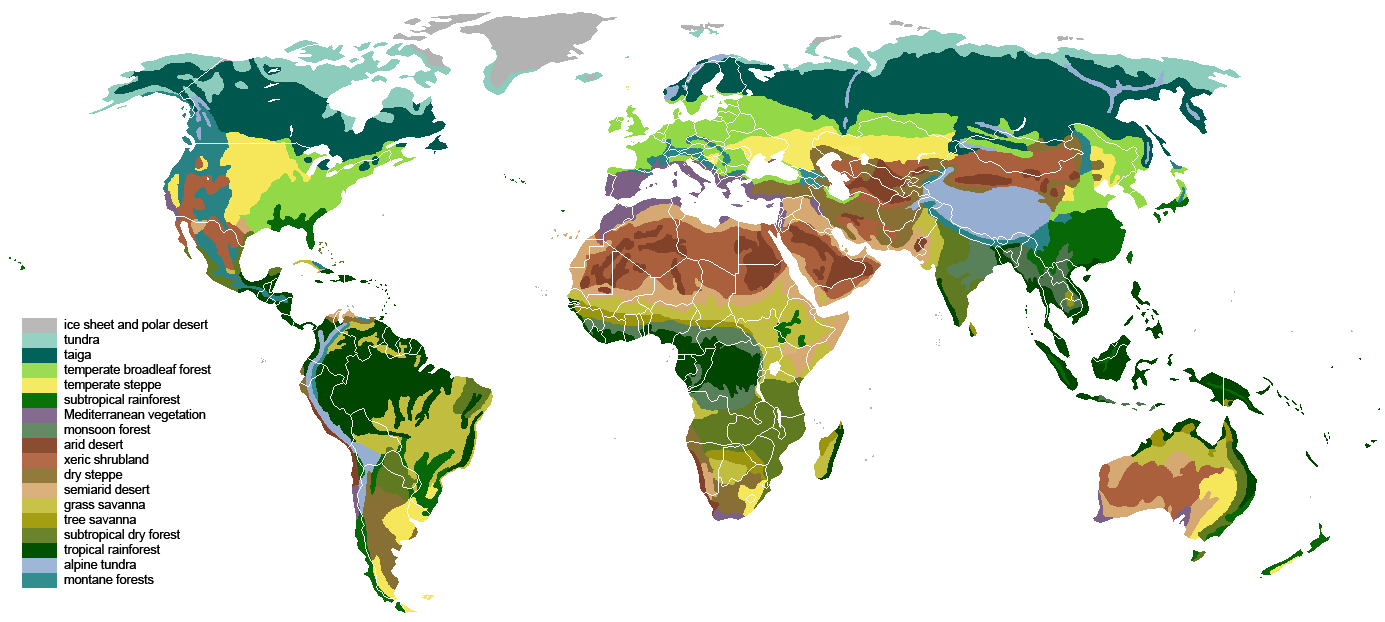

A biome is a community of plants and animals that have common characteristics for the environment they exist in (Figure 2.1). They can be found over a range of continents. Biomes are distinct biological communities that have formed in response to a shared physical climate.

The principal biome-types are Tundra, Taiga, Deciduous forest, Grasslands, Desert, High plateaus, Tropical forest, and Minor terrestrial biomes.

Figure 2.1: Mapping terrestrial biomes around the world

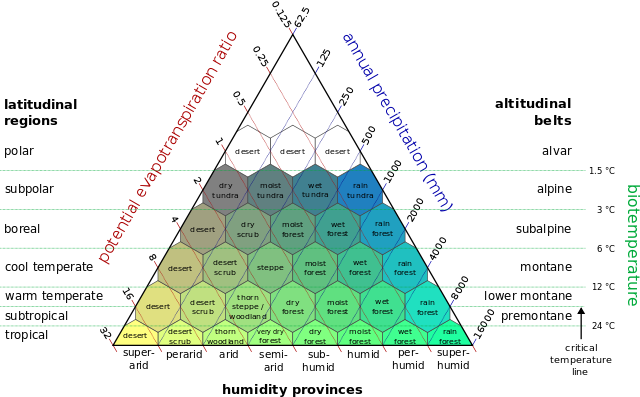

Holdridge (1947; 1967) classified climates based on the biological effects of temperature and rainfall on vegetation under the assumption that these two abiotic factors are the largest determinants of the types of vegetation found in a habitat (Figure 2.2).

The three axes of the barycentric subdivisions are 1) Precipitation (annual, logarithmic) 2) Biotemperature (mean annual, logarithmic), and 3) Potential evapotranspiration ratio (PET) to mean total annual precipitation.

Further indicators incorporated into the system are 1) Humidity provinces, 2) Latitudinal regions, and 3) Altitudinal belts.

Figure 2.2: Holdridge life zone classification scheme.

2.2 Internal environment

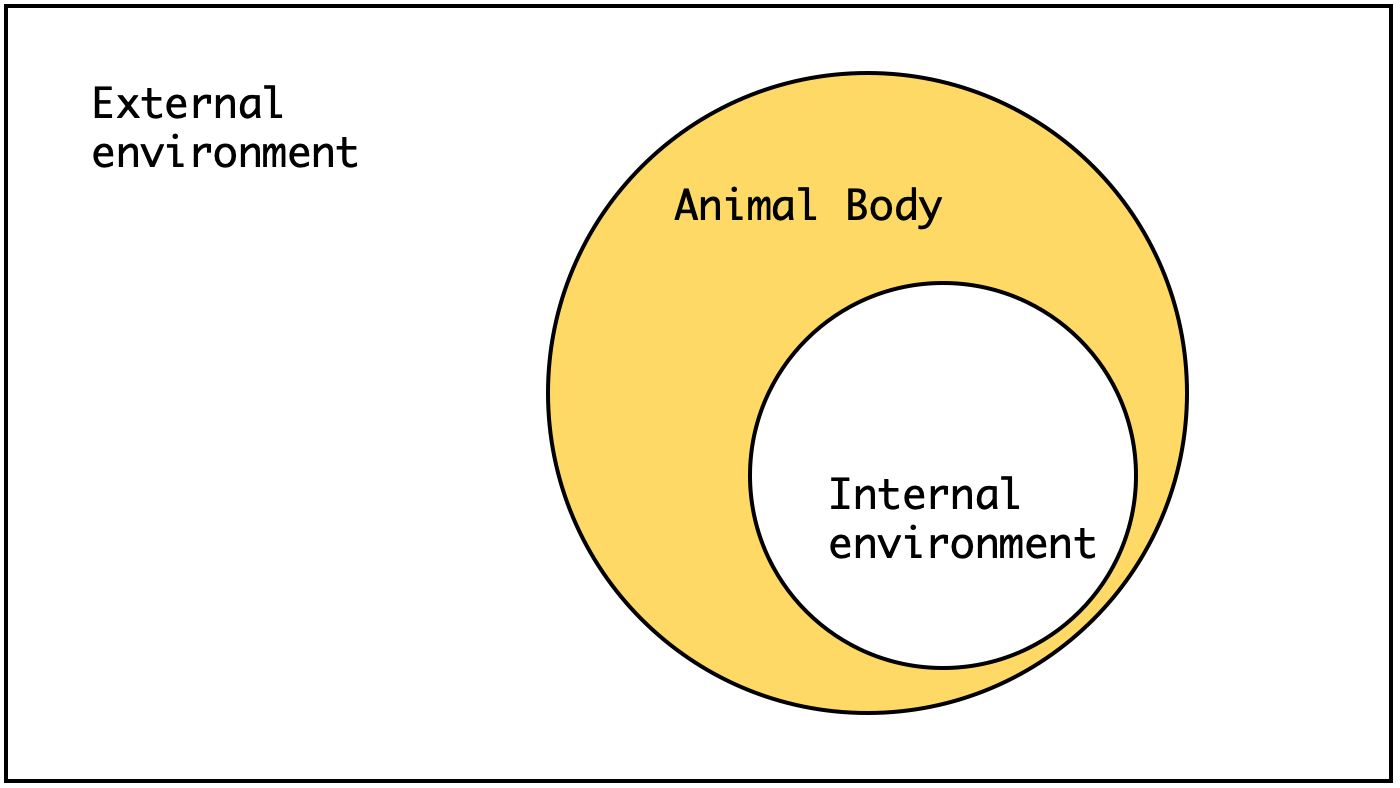

“The living body, though it has need of the surrounding environment, is nevertheless relatively independent of it.” — Claude Bernard

Higher animals have complex systems that respond to stimuli to perform their essential body functions. When the animal receives the signals from the sensory organs, they produce a local reflex action and/or react in the central nervous system. Weak signals produce no responses, but strong stimuli change the physiological or behavioral status of the animal.

Figure 2.3: External and internal environment

2.2.1 Shelford’s law of tolerance

“Each and every species is able to exist and reproduce successfully only within a definite range of environmental conditions.” — Ronald Good

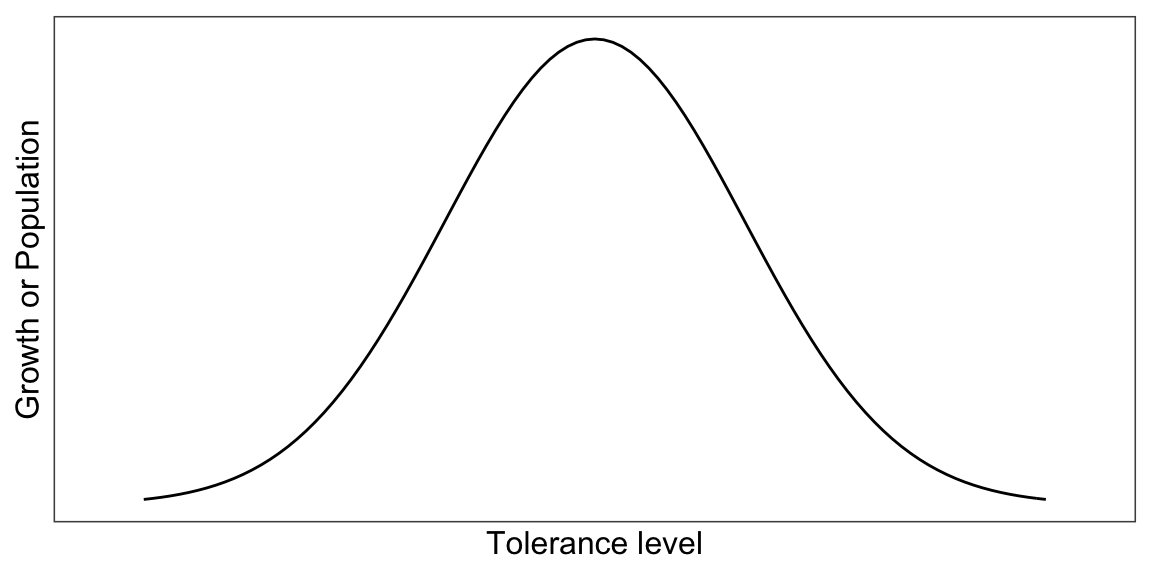

Although external environments are continuously changed, if animals in the normal status, they keep the composition of the extracellular fluid (internal environment) constant to maintain their life. We call it homeostasis.

However, the capacity to maintain the homeostasis is broken when the animals let the harsh environments and differ by their species. Animals may be limited in their growth and their occurrence by the minimum, maximum, and optimum condition (Shelford 1931) (Fig. 2.4).

| Control variables |

|---|

| Core temperature; Blood glucose; Iron levels; Copper regulation; Levels of blood gases; |

| Blood oxygen content; Arterial blood pressure; Calcium levels; Sodium concentration; |

| Potassium concentration; Fluid balance; Blood pH; Cerebrospinal fluid; Neurotransmission; |

| Neuroendocrine system; Gene regulation; and Energy balance |

Figure 2.4: Shelford’s law of tolerance

The optimum range of environmental condition may differ within the same organism, and it is not necessarily fixed. They can change as:

- Change of seasons

- Change of environmental conditions

- Life stage of the organism

2.2.2 Adaptation

“Changes in morphological, anatomical, physiological, biochemical and behavioral characteristics of the animal which promote welfare and favor survival in a specific environment.” — Hafez

Hafez and others (1968) defined an adaptation as above. The adaptation helps an animal survive in their external environment. The representative adaptive traits are:

- Structural adaptation

- Behavioral adaptation

- Physiological adaptation

Structural adaptation is the changes in physical features (e.g. body shape, skin, and internal organs) of the animal. Behavioral adaptation is the changes in behaviors (e.g. searching for food, mating, vocalizations, and mitigation) of the animal. Physiological adaptation is the changes in the animal body functions such as growth, temperature regulation, and ionic balance. Sometimes, adapted animal create a new species (speciation).

2.2.3 Acclimatization

Acclimatization is the physiological changes induced by a complex of factors such as altitude, temperature, humidity, photoperiod, or pH. Acclimatization is the short-term process (hours to weeks) by comparison with adaptation (take place over many generations).

Figure 2.5: Migration is an example of a behavioral adaptation. Grey whales swim from the Arctic to Mexico every year.

References

Hafez, Elsayed Saad Eldin, and others. 1968. “Adaptation of Domestic Animals.” Adaptation of Domestic Animals. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Shelford, V. E. 1931. “Some Concepts of Bioecology.” Ecology 12 (3): 455–467.